Migrant Seasonal Workers Exploited While Supermarkets Profit

A new report has revealed the structural drivers of exploitation in the supply chain and migration system for migrant workers employed on large soft fruit farms. The Landworkers’ Alliance, in conjunction with the New Economics Foundation, Focus on Labour Exploitation, Sustain, the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants, and a network of former farmworkers, launched the report to show the extent of the exploitation and makes a series of demands for reform.

Workers indebted from the outset

The new Seasonal Workers Visa was introduced to fix the lack of farm labour after Brexit and now covers the migration of 57,000 farmworkers, who can stay for a maximum of 6 months but must pay the cost of travel and visa application fees upfront.

Many workers incur debts to meet these costs. A third-party recruitment agency acts as their visa sponsor and exercises a huge amount of control over the workers during their stay in the UK. The report found that the scheme is creating an indebted workforce tied to its employer, with only a limited time allowed in the UK to work hard enough to pay off the costs of migrating.

The visa contributes to poor working conditions

Using the testimonies of former farmworkers, the report demonstrates how structural failings in the visa have caused poor working conditions. These workers are not just passive victims or just ‘labour’ inputs into the agro-industrial system; the report shows that they are people with interests, agency, and desire to change things.

A former farmworker from Nepal described how they became ensnared in debt bondage to a third-party agency. They were approached by a broker from the agency who offered them a place on the scheme in exchange for a large sum of money and control of the worker’s passport. The worker ended up paying £4,353 to the broker and could not earn enough money to pay off their debts.

Long hours and low pay

Life on the farm for migrant workers means extremely long hours; with consecutive 14-hour days, no rest days and punitive unpaid time off if picking targets of 20kg an hour are not met. Workers also experienced systematic non-payment of wages and bonuses and abuse from supervisors. The workers have, however, resisted this with attempted strike actions and go-slows.

How does big business profit?

Our research demonstrates how this exploitation translated into monetary benefits for companies along the supply chain by using a case study from a farm in Kent. A worker picking soft fruit retains just below 8% of the total retail price of the produce. That means when you buy a £2.30 punnet of strawberries in the supermarket, the worker keeps 18p after costs, while the supermarket gets £1.26 of which 14p is profit, the farm gets 50p of which 5p is profit, and the packaging and distribution firm gets 10p.

After the costs of travel and migration, food, subsistence, rent, and National Insurance, workers were left with just 7.6% to send home. The graphic below illustrates the findings and shows what workers earn per punnet of strawberries produced at this farm.

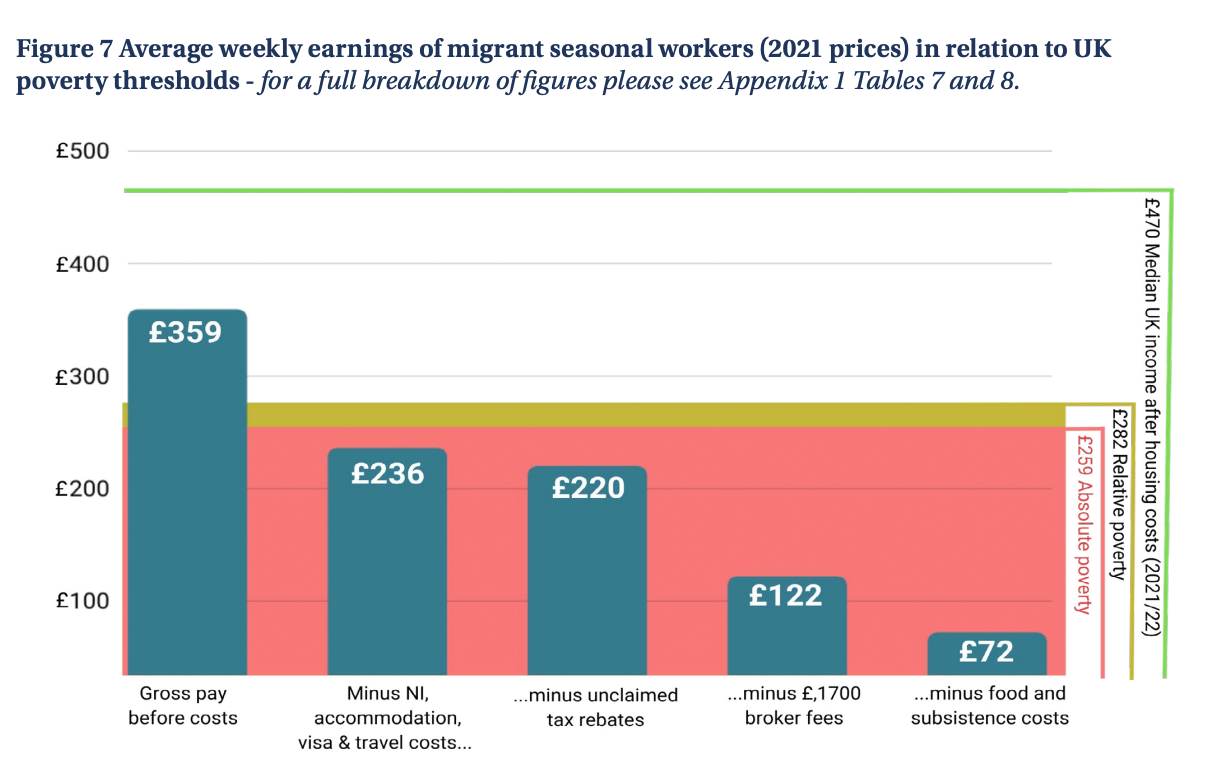

This is reduced further if fees to third-party brokers are paid. Workers paid £1,700 retain just 2.9%, and if they pay £5,000 upfront, they lose money coming to the UK, retaining -4.9%. The graph below shows that the weekly earnings of workers are below absolute poverty thresholds in the UK, with earnings of just £236 per week after accommodation, national insurance, visa, and travel costs.

Average weekly earning of migrant seasonal workers (2021 prices) in relation to UK poverty thresholds.

Gross pay before costs - £359

Minus NI, accomodation, visa & travel costs - £236

Minus unclaimed tax rebates - £220

Minus £1,700 broker fees - £122

Minus food and substinence costs - £72

Alternative Approaches to migrant labour

Alternative approaches have been pioneered by tomato workers represented by the Coalition of Immokalee Workers in Florida (CIW). They campaigned for fast food companies and supermarkets to fund wage increases and work with farmworkers to improve conditions. This led to 14 leading buyers and 90% of tomato growers in Florida signing up for the CIW's Fair Food Program. It leverages the power of buyers to improve standards.

The agreements mandated supermarkets to pay extra to fund wage increases and to not source from farms that violate these agreements until they are back up to code. This system has resulted in pay increases of 25-50% for workers, and greatly reduced incidents of forced labour, sexual violence, wage theft, and intermediary fees.

Demand for reform

Our report calls for urgent reforms. First that supermarkets pay extra to fund wage increases and compensation for defrauded workers. Second, the government moves away from temporary migration schemes and works with current and former farmworkers to develop new approaches to seasonal labour migration, and finally that a farmworker organisation is established to provide immediate support for workers and to campaign for better conditions.

You can read the full report online here.